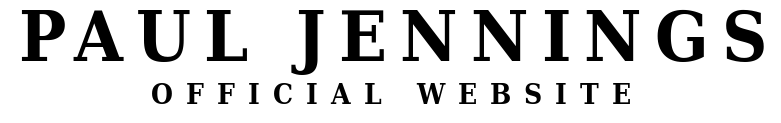

The Lorikeet Tree

Most of my stories originate from one small idea or event. I can say, right now, that finding one of these gemstones is the hardest part of the writing process. For me it is agony. I know that some authors like Enid Blyton and Ray Bradbury have said that ideas flow like magic but I think that writers like this are in the minority. Most of us struggle to find something fresh and original to write about.

When I have finally come up with an idea, I sometimes begin sketching out a plot. At other times I just begin writing without knowing how the story will develop. Usually, I don’t know what the tale is all about until I finish. Often, I am amazed at what I discover in my own books.

After about ten years of writing, I realised that I was unconsciously returning to a small number of themes. The most common of these related to the separation of parent and child. To me, this is the most powerful theme about which one can write. I have had scores of moving letters about tales which seem funny, but in reality, contained moving content about human nature.

The Lorikeet Tree once again is a riff on my most used theme. But in other ways it is different. The two teenagers in the story have no mother and in the first line of the book we find out that their father is dying. It seems that, unlike my previous stories, there will be no uplifting reunion.

Am I transgressing any rules by writing about death for younger readers? I think that it is acceptable. By the time we are twelve or thirteen we know that death is a reality. Pets die. And grandparents. Fatal car accidents fill the news every day.

How should I as an author handle this? Is there ever happiness in life after the loss of a loved one? Is there an afterlife? How can we keep going? Does anything remain in us that was once part of someone we loved? How should we behave at such times?

Literature tells us how others have managed. It offers solace and help.

Some of my readers might not go past the first sentence in The Lorikeet Tree. This is a risk I have taken because I hope that my story, besides being about ordinary people who discover what is important in life, is filled with adventure and excitement.

Having finished the book I can see that, without meaning to, I have written about courage, the environment, hope, mental health and - most of important of all - love.

The Lorikeet Tree is the most biographical of all my stories. It is set in a developing forest along the Great Ocean Road near the country town of Warrnambool. I established such a forest there more than thirty years ago and have enormous feelings of attachment to it. The memories of the re-introduced native bushland on that property enabled me to start the story in a setting with which I was totally familiar.

My protagonists are a teenage girl who loves a wild bird that has been attracted to the area, and her twin brother who is smitten by a growing kitten. Angry exchanges result in life-threatening conflict and thoughtless reprisals. Cat and bird, both driven by instincts, merely want to survive but more is demanded of the two teenagers who must somehow solve their problems with love for each other, their father, and the natural environment in which they live.

In The Lorikeet Tree, cat and bird serve as a metaphor for the struggle between brother and sister. Can such a story have a happy ending on both levels?

All I will say is this. Upon reading the first draft, my editor Julie Watts, made the following comment, “Once again we are all reaching for the box of tissues, Paul.”

That’s good enough for me. There’s nothing wrong with happy tears.

Paul Jennings

My Biography

I started trying to write a biography more than ten years ago but I just couldn’t find the right voice. I would write a few chapters and send them to my editor, Julie Watts. Each time, as always, she was encouraging but I knew in my heart that my efforts weren’t good enough. The work always seemed boring and stilted. Then, early last year (2019) I thought to myself, ‘I’ll try and make it read like a novel. I’ll shift things around a bit and sow a few clues as to what might be going to happen next. I decided to use the techniques that I usually adopt when writing fiction.

I also thought that I would throw in a few tips about writing for kids and some insights into the world of children’s publishing. In addition, I made a vow to let many of my foolish behaviours and secret problems show through. I thought, ‘What’s the point of a memoir if we are not going to share our vulnerabilities and frailties?’

With these thoughts in mind I wrote two sample chapters and sent them to Julie. She said, ‘You have hit the mark this time Paul. I would like to send it to Erica at once.’

Erica Wagner is my publisher. She read the two chapters on the tram and rang me straight away. She said, ‘I have to check with the boss, but I want to publish this book, Paul.’

I was so thrilled and went straight to work. Untwisted has definitely been the most difficult book I have written. Not just because it was the longest (76000 words) nor because it is aimed at adults. But because there are so many problems to face when writing about the past that are not there when one can make the whole story up (as in fiction). So, I decided that I would also share these problems with the readers as my story unfolded.

Now I have finished, others will make their judgements in regard to my success. My publisher Erica sent copies of the manuscript to some literary experts and asked for their opinions. I am sincerely grateful to these people for reading the whole book and offering these generous comments.